This article will be going over how our mind responds to stress and how it relates to mental health. I will be discussing the Limbic System and how it contributes to the fight, flight, or freeze response and how this process may affect those with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder or Generalized Anxiety Disorder. I will then discuss the different treatment modalities that can help.

The anatomy of stress.

Every minute, our body receives sensory input from the outside world through our five senses: touch, taste, sight, hearing, and smell. This information is converted from a manual input to an electrical signal by the brain and that signal is sent through the Limbic System. If the brain senses no danger, it then sends the signal to the Prefrontal Cortex, which decides on how to proceed in most circumstances.

Every minute, our body receives sensory input from the outside world through our five senses: touch, taste, sight, hearing, and smell. This information is converted from a manual input to an electrical signal by the brain and that signal is sent through the Limbic System. If the brain senses no danger, it then sends the signal to the Prefrontal Cortex, which decides on how to proceed in most circumstances.

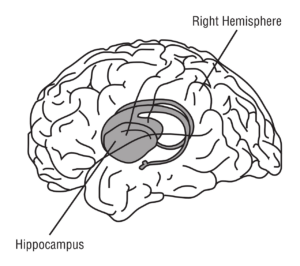

The Limbic system is in the middle of the brain and is comprised of the Hippocampus, the Amygdala, and the Pineal Gland. The Limbic system is typically responsible for regulating memory, sleeping, and mood.

When the sensory signal travels through our brain, it travels through our limbic system and then to the Prefrontal Cortex. The Prefrontal Cortex is responsible for executive functioning, such as making decisions and delegating tasks.

While the signal is passing through the limbic system, our amygdala is looking for signs of danger in the form of a dangerous odor, color, oncoming threat, or potential accident. If the amygdala senses danger, it releases cortisol, a stress hormone. This stress hormone travels to our adrenal glands located on top of our kidneys.

Once the adrenal glands receive cortisol, they start to signal the release of glucose. Glucose is what our body breaks food down into and our adrenal glands call for its release when it senses distress because it recognizes the need for energy if we have to run away from something because we’re being chased or the need for body fuel if we have to fight off an opponent.

This process is typically known as the fight, flight, or freeze response. During this process, the amygdala tells the prefrontal cortex that there is no time to think intently about a situation, instead there is only three possibilities: to fight the threat, run away from it, or play dead.

This process is typically known as the fight, flight, or freeze response. During this process, the amygdala tells the prefrontal cortex that there is no time to think intently about a situation, instead there is only three possibilities: to fight the threat, run away from it, or play dead.

During this time, the prefrontal cortex goes offline as the amygdala starts releasing cortisol, which is why most people have difficulty making good decisions when they are upset or remembering parts of a traumatic experience. Because the prefrontal cortex is responsible for making executive decisions and it goes offline, we aren’t utilizing the same resources when we are stressed as opposed to when we are calm.

As the brain releases cortisol and our adrenal glands start to release glucose, our body uses this energy to gear up just in case we have to fight or run away, meaning our heart race begins to increase and our muscles become tense.

The emotional side of stress.

In this excited state we can become more irritable and use a shorter tone with people because our body is responding to stress and our prefrontal cortex isn’t responding as it typically does. This response normally lasts for 15-30 minutes. After that time, if our brain senses that the threat has passed or we have gained safety, the amygdala turns off the cortisol while our heart and muscles burn up the last of the glucose.

As the cortisol shuts off and the glucose is used up, our heart rate starts going back down and our muscles feel less tense. If we were engaged in strenuous activity during the flight, fight, or freeze response, our muscles may feel sore from the build-up of lactic acid, a byproduct of our muscles being in use for extended periods of time.

For individuals with Generalized Anxiety Disorder or individuals who have a history of trauma, the fight, flight, or freeze response can be experienced more frequently than average. As van der Kolk (2014) explained, those who are used to being in constant danger or perceiving constant danger may have limbic systems that are more readily activated because of conditioning.

For example, if someone grows up in an environment that is typically frequented with peril, such as that of an abusive household or perhaps a city in which there is a high prevalence of crime, then that person’s limbic system might be more activated than the average person’s as that person’s limbic system has been conditioned to be more alert for possible danger.

For example, if someone grows up in an environment that is typically frequented with peril, such as that of an abusive household or perhaps a city in which there is a high prevalence of crime, then that person’s limbic system might be more activated than the average person’s as that person’s limbic system has been conditioned to be more alert for possible danger.

This is an advantage if that person continues to exist in that dangerous environment because it helps to keep the person alert to danger. On the other hand, if that person leaves that dangerous environment and settles into a place that is relatively safer and more stable, that active limbic system state may start working against the individual because they may experience overstimulation to things that may have been threatening in the past but aren’t anymore.

As mentioned before, one of the parts of the limbic system in the Hippocampus, which is the region of the brain responsible for storing memories. When we are stimulated by an event that produces the fight, flight, or freeze response, the brain highlights the sensory input it’s receiving for later use. For example, let’s say that someone grows up in an environment where if they fail to wash the dishes correctly, they are punished harshly.

After a time, the brain will begin to associate dishes with danger to the extent that whenever that person is doing dishes, they can’t relax or stop washing it until it’s gleaming. It may also present as someone feeling tense or anxious around dinnertime for no apparent reason and upon introspection that person discovers that they feel tense around having to do dishes after the meal is done.

Treatment for stress.

It can be difficult to pick up on these patterns as they can be subtle, that’s why monitoring is helpful. EMDR can be a helpful tool in addressing these states as well as distress tolerance tools including deep breathing, which works to recondition somatic responses, such as increased heart rate and flightiness, related to the limbic system response.

The more we are able to consistently redirect or redirect energy brought on by the limbic system, the less the limbic system produces an excited response as it’s desensitized to the trigger.

The more we are able to consistently redirect or redirect energy brought on by the limbic system, the less the limbic system produces an excited response as it’s desensitized to the trigger.

As mentioned before, the adrenal glands send out a signal that releases glucose into our bloodstream, which is what our body uses to create energy, which is why exercise is also heavily suggested for those that experience PTSD or anxiety, as it helps to metabolize the excessive glucose released during the fight, flight, or freeze response.

Certain mental beliefs can also stimulate the limbic system. For example, if I have the belief that I will embarrass myself if I engage in small talk with others, then every social situation will feel like a threat and my limbic system will become activated during social situations, giving me the feeling that I should leave the conversation or perhaps map out how I might avoid social situations in general so that I won’t risk making a fool of myself.

This can result in isolating behavior and me missing out on meaningful conversations and relationships. A helpful way to address this is through Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, which works to identify such beliefs and reframe them in a rational matter.

This may look like understanding that not every social interaction will result in an embarrassing circumstance and working to identify ways in which I might contribute to healthy and positive social interactions are ways to help me feel more comfortable in social situations and less like running away from them.

Counseling.

At the end of the day, if you feel like you might experience the fight, flight, or freeze response more often than is normal or more often than contemporaries, it may be signs of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder or Generalized Anxiety Disorder and you may benefit from exploring these possibilities with a licensed professional.

Photos:

“Human Brain”, Courtesy of OpenClipart-Vectors, Pixabay.com, CC0 License; “Broken Plate”, Courtesy of BRRT, Pixabay.com, CC0 License; “A Spoonful of Sugar”, Courtesy of designfoto, Pixabay.com, CC0 License; “Freaking Out!”, Courtesy of Erika Wittlieb, Pixabay.com, CC0 License